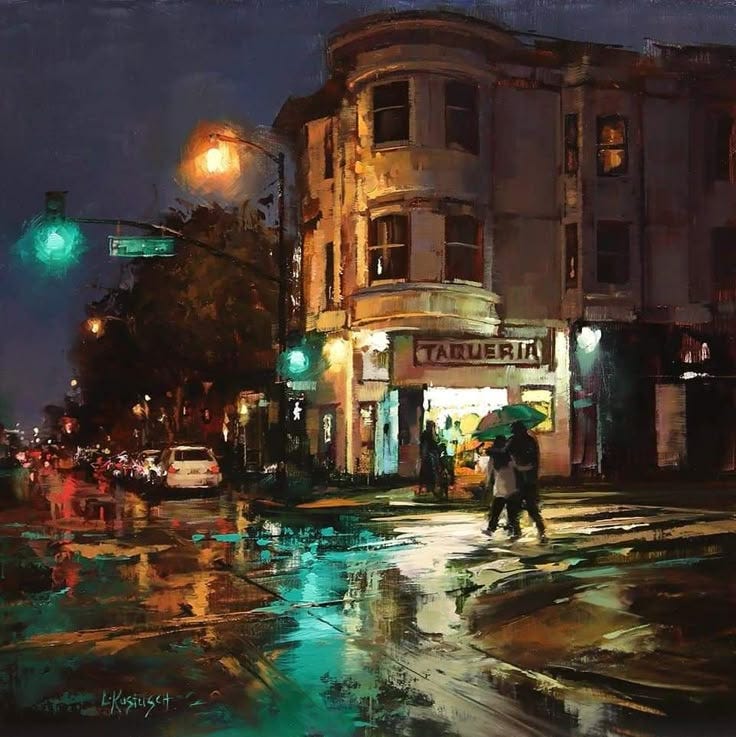

Mission Hills, San Diego, late August 2022, well into the night, the clock past 1:00 a.m. but the sky not dark, never dark, never black but faintly orange and starless with the distant nonstop glow of yellow street lights and red-eye stoplights and stark-white LED headlights, moving, buzzing, flickering, stopping time in the hot summer of the night; quiet, here, on this street, murmured voices behind the door, car passing, stopping, idling, air damp with the tail-end of a tropical storm passing by, lost somewhere over the lukewarm sea.

Truck door closes. Engine starts. Swing a U-turn over the double-yellow line, two minutes to home. There, a late-night walker with a small hairless dog. There, a coyote, casual, looks over its shoulder, evaporates into the brush down a dead-end road. There, a man asleep under a bus stop bench. The overpriced café blank-eyed, chairs upside-down on the tables. Wedding dresses still white shadows in the bridal shop. Truck’s radio turned down.

Seven streets down. Turn left.

Parallel park. Scrape the curb. Try again. Crooked—good enough.

Home is 200sq. feet. Mushroom curtains over open windows. Facebook-marketplace furniture. Antique botanic prints on the walls. A straw hat. A bathroom door that opens halfway, hits the toilet. The screen on the kitchen window falls out, lets in bees that have to be gently guided out again. Can see dead grass and dirt under the floorboards through the cracks.

Mission Hills, San Diego. Subdivision map #1115.

Below: Old Town, Downtown, the harbor.

Streets named after birds. Falcon Street. Goldfinch. Ibis. Jackdaw.

A list of ghosts. Violet Whaley. Yankee Jim. Madame Tingley. The White Woman.

I don’t believe in ghosts. Not really. I like the idea of ghosts—friendly ones, mind you, the ones who linger about in cracks and corners, creaking open doors and shifting dishes in the drying rack, unseen shadows only the cat knows is there. I like the idea that ghosts happen where the walls of time are thin, where you might catch a glimpse of a previous occupant going about their lives, in their own time, a moment overlayed.

But San Diego is full of ghosts.

Proctor Valley Road. A lonely five miles of rough, bumpy dirt road connecting Eastlake and Jamul. Decades of ghosts, ghouls, monsters. Some brush, some trees, no lights. We drove there late at night, dressed in black, like robbers or urbexers, but it was more for the thrill than anything else—and maybe not the best idea, as police and Border Patrol have been known to prowl about. But it was the ghosts we were thinking about. We bumped a few miles down the road before turning off the car and stepping out. We swept our flashlights over the barbed wire fence toward the hills. A pause, a wavering, when we caught sight of Something in the beam of light. A laugh when it was only a stump. Switching off the flashlights and daring each other to shout into the dark. Disappointed, and relieved, when nothing called back to us.

They say headlights, attached to no car, will try and run you off the road. That your engine will break down and small dusty hand-prints will appear on your windows. They say there’s blue people who live in the brush. They say a woman in white screams like a banshee. That people were hung from that tree. That here, men have been murdered.

Cabrillo Hall, PLNU campus. Madame Katherine Augusta Westcott Tingley lived there once, before it became classrooms and offices. She was the Outer Head of the Theosophical Society and founder of the International Brotherhood League. Raja-Yoga School and College. Theosophical University. The School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity. She is said to wander what used to be the second-floor balcony of the house, creaking floorboards as she paces, though she died 5,500 miles away in Sweden. I spent a semester in one of the classrooms. Freshman comm class. I was a senior and didn’t pay attention. But I never heard madame Tingley, either. The steps of the building are too short and wide—she wanted to reincarnate as a turtle, the story goes, and made the steps to suit her future figure.

Pioneer Park, built over an old graveyard, the headstones shifted to the fringes of the park. Whaley House, the most haunted house in America, and the nearby El Campo Santo Cemetery. The Star of India, the oldest active sailing ship in the world, where I worked for a few months. Hotel del Coronado. The Gaslamp Museum. Faze Rug Tunnel. Cosmopolitan Hotel. El Cortez Hotel. The lighthouse. Cave 7. Tunnel 2.

San Diego is full of ghosts.

California cities are peopled places, rough-around-the-edges places, massive get-yourself-lost places. We don’t do things by halves, there. There’s space—we use it. Thousands move in. Thousands move out. There must be a reason that these places—cities and towns, forests on the edge of the urban, drain tunnels slathered with graffiti, hotels along seafronts—have so many of these ghosts. These are places where more people have lived than died. Places deeply entrenched in story and living, with doing and saying and wearing down, experiencing and remembering. Marked by the scrape of shoe-heels and hands. I think this is where they come from, the ghosts. If you live in a place long enough, you’re bound to leave a little something when you go, tangible or not. Or maybe you are still there, in a way. Seen through time, in another time, your past and someone else’s present intersecting, just for a moment.

Three and a half years is a short time to live in a place, but long enough to shed a little of oneself into the concrete, to leave bits and pieces behind. Memories here and there. Footprints in the dirt along Sunset Cliffs. A donated sweater still hanging at a thrift store. A face in the background of a yearbook photograph. A name in a newspaper byline. The smell of chili cooking in a studio on Jackdaw Street. Holes in the wall where pictures hung. A held breath in the hold of a ship, listening to the sound of pistol shrimp echoing like retroflex clicks on the other side of an iron hull. A shadow walking down Proctor Road, a laugh in the dark across time.

Ghosts don’t happen where people died.

Ghosts happen where people lived.

Someday I might go back there. I’d like to see those haunted spots I didn’t have a chance to visit before I left. But I think I’m more likely to see ghosts in different places—the ones I already know.

I’ll go back and see them sitting at the coffee shack on corner of Fort Stockton and Goldfinch, or congregated in classroom BAC104 whispering about the shape of narratives and passage of time in words. I’ll find ghosts wandering the park and the thrift stores, getting burritos at Las Brasas. Trying hot sauce that’s a little too hot in Old Town and drinking root beer to cool off. In streets I could drive with my eyes closed, in night skies too lit by the lights of downtown to know stars. In the taste of that chai-and-coffee iced drink I’ve never known anywhere else, in lavender-honey ice cream and boardgames and movie nights in the campus lounge where a running commentary is kept up through the whole of the film. In the wildly colored, busy streets of Hillcrest and that one stoplight that was, always, timed very badly with the one that came before it, in the field at Petco Park with the faint drifting notes of a long-over concert. In music and food and photographs and memory, in voices I haven’t heard in a long, long time. In a city unsleeping. Down ghost roads where there are no ghosts but my own, moving through a past life.

Mission Hills, San Diego, 1:00 a.m. on a hot summer night. U-turn over the double yellow line. Seven streets down. Turn left.

Two minutes to home.