Brighton, 10:00 a.m. on a winter day. White, wind-battered seaside hotels overlook a cold, browned sea, and the pier stretching out across the water like an endeavor to bridge the Channel. The miniaturized amusement park at the end of the pier is blinking, red and yellow bulbs fringing every ride, music playing loudly over the sound of the waves breaking on the piles fourty feet underfoot. Carousal ponies stand still, frozen in mid-prance with staring, painted eyes. The Cup n’ Saucer, Crazy Mouse, and and Turbo Coaster are locked, silent. Candy-floss booths are closed. The arcades are festooned with clown faces and circus-font names of games that’ll steal your quarters and, occasionally, of you’re lucky, spit out factory-made plastic prizes. A security guard wanders, looks spiffy in his tilted cap and dark blue uniform against the empty backdrop of what has the look of an abandoned carnival, beneath a grey, grey sky. There is a feeling of unbelonging. Of something wrong. This place, though I have never been here before, is made for people, for crowds, for the smell of fried food and the bumping of shoulders, for shouting over music and voices, for no quiet places. But now, in winter, it lays still.

I have felt this before. A county fairground out of season in the early morning, walking in a low, heavy mist, obscuring even what ghosts might live there that time of year. An empty dorm in San Diego at the end of term, old beach towels hanging forgotten over balcony railings, the laundry room scattered with the tops of detergent bottles and lost socks, washer doors half-open and stinking with must. It is what John Koenig calls, in The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, by the name of kenopsia.

You can sense it when you move out of a house—noticing just how empty a place can feel. Walking through a school hallway in the evening, an unlit office on a weekend, or fairgrounds out of season. They’re usually bustling with life but now lie abandoned and quiet.

John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

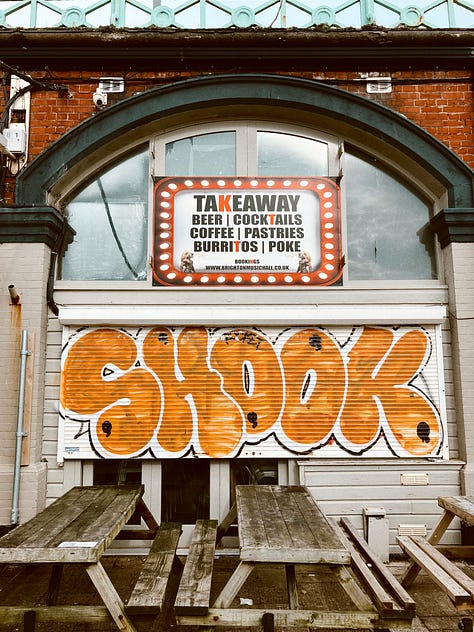

Brighton is an eclectic city of bright murals and salt-eroded buildings, untidy, grungy, abraded, gnawed by the wind and the sea with no smooth edges. It is slathered in spray paint and sticker adhesive, bulletins pasted into brick by the rain, cigarette butts smashed like mortar into the cracks between flagstones, tags and messages and QR codes plastered everywhere there is space to display them. Murals show scenes of circus acts, squirrels and dragonflies the size elephants, disembodied heads with limbs coming out the ears; everything, all of it, worn. What will this place look like in fifty years, in one hundred? What will happen to Brighton, the nonconformist, idiosyncratic, eccentric San Fransisco of the UK, if its inhabitants vanish tomorrow? Surely, it will take a millennia for nature to reclaim this stretch of the coast. Such a tight mesh of streets and layering of concrete will not give up easily. But it will, eventually.

In the absence of us, parks and gardens will grow wild, escaping their boundaries to push up cobblestones and paved ways, making way for bluebells to grow where roots have pushed up walking paths. The Royal Pavilion will be overtaken by vines, shaded by tree and branch. Broken glass will let in rain and light, so that grass and lichen may grow across the floors of museums, reclaiming space, cleaning air. Birds will build nests in the arms of statues.

In the absence of us, the rocky beaches will be battered by storms. Sea-walls will crumble. Seafront shops will flood, spewing coffee machines and cheap souvenirs of rubber magnets, stamped coins, and plastic flip-flops into the water, where they will be carried abroad to the shores of France or Spain. The Palace Pier will wear down, over time, until it looks as the old West Pier does now—the skeleton of some old giant laid out to bleach in the sun, dissolving under salt and wave. The shape of the coast will be changed, not by the fashioning of human hands, but by the temper of weather. Maybe, eventually, Brighton will be gone forever, wiped off the face of the earth, made into sand.

In the absence of us, the world may be reclaimed.

But it will never be the same as it was before it was touched by our hands.

Human industry has changed, and is continuing to change the world. Even if we were all to be wiped out tomorrow—factories falling silent; generators shuddering to a halt; cargo ships drifting and colliding, sinking to the seabed, sending sediments billowing—we have set in motion evolutionary forces that will continue to act upon the genetic makeup of almost every other species alive on this Earth. They shape-shift and metamorphose, transmute and adapt, in ways that we cannot anticipate and certainly cannot control. They want to live, if they can.

― Cal Flyn, Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape

In conservation we talk about passive and active wilding—do we let abandoned places find their balance, to discover equilibrium on their own, or do we intervene, as we always do, and manage the land as best we can? The problem with passive management of land to restore—or, to put it simply, doing nothing and letting ‘life find a way’, is that we have already changed it, and it cannot go back to ‘normal’ by itself. We have made too much of an impact.

Abandoned farmland will not revert to natural woodland by itself, not with exhausted soil, invasive species, and rerouted streams. It can’t go back to Bronze Age woodlands when Bronze Age herbivores have been hunted to extinction. The truth is, the world doesn’t know itself without us. Dartmoor used to be woodland. The chalk downs of south Kent never used to exist before humans changed the landscape, and we try and protect them from being wooded over. Both are now viewed as biodiverse, ecologically important areas, even shaped as they were by our hands.

A kenopsic world is a coin with two sides, a double-edged sword, a paradox.

A post-human landscape is an eerie, quiet thing. Beautiful, yes, but not natural. Empty of humans, it will not go back to how it was ‘before’, because there is no before. There is only now, and the future. We were always here, and we will continue to be here, and we will continue to build our cities and towns. We are not meant to leave what we have wounded to heal itself. We are meant to be stewards. We are meant to reverse the damage we have done, to doctor it, to restore it. It is our job to fix what we have broken— ‘the heaven, even the heavens, are the Lord’s; But the earth He has given to the children of men’ (Psalm 115:16, NKJV). It’s our inheritance. Our privilege.

There’s a certain school of thought that comes up when we discuss the current ecological crisis: humans are bad, nature is good, and the world would be better off without us—a romanticizing of post-human dystopia that only a few survivors get to enjoy, a thinking that we are capable of nothing but ruin and nature can only exist as wholly natural in the absence of our presence. But that is not so. We are to the earth as a lion is, as a blackbird, as an earthworm, as an amoeba. Yes, maybe the planet would be prettier, quieter, and cleaner without us. But it would still be changed—irrevocably. Without humans, Brighton will not fall quietly into the sea and leave behind a green earth. It is alive as an ant hill is alive, and that is ok. That is how it is meant to be. We can find other ways, active ways, to make our cities greener and cleaner, in a world we exist in, too.

In the absence of us, what is left is scarred, decayed, and wounded.

In the presence of us, there may be found renewal.

I have only a one word comment - FANTASTIC!!

Beautifully and honestly written.