Dear Readers,

After a short break over the holidays, posts will now resume weekly. My plan for the next few months is to take one day every weekend to go out into the world, to immerse myself in nature and history. I’m sure some writing will come of it. The only way to know the world is, of course, to live intentionally in it. Thank you coming along with me.

In the last month I have traveled over 11,000 miles by way of plane, car, bus, train, and ferry. Twice, I have flown over the Atlantic and the entirety of North America and twice I have crossed the English Channel. This only took an accumulated four days. Four days to go halfway across the world. Four days to use 2.7 tonnes of energy. For those four days, I watched movies and slept, played gin rummy and read a book or two, and essentially took no notice of the forward momentum that was responsible for sending me across the planet at over 500mph for 10 hours, or across the Channel (at a much less impressive but just as lengthy 18mph for 10 hours).

We live in an era where we essentially have access to teleportation, an idea which would have astonished anyone before the turn of the 20th century when horses and carriages were still the most common type of transportation and trains were for the wealthy. Now, we embark on a plane, close our eyes, and wake up in other city a few thousand miles away from home, a luxury and convenience which has slowly, but surely, become so normalized it has become an inconvenience. Despair over a long flight with uncomfortable seats. Sighing over a 10 hour ferry trip when a 1 hour plane flight would have taken so much less effort and time (but would have been much less sustainable). We depreciate both the wonder of travel and the process of our own bodies’ movement—or as C.S. Lewis puts it, we have ‘annihilated space’ by accepting, and complaining over, the ease of modern travel, destroying the concept of space and distance by doing so. Maps have been crumpled. Road names forgotten, or never learned. Landmarks passed over. The in-between is unknown, pushed away.

The truest and most horrible claim made for modern transport is that it “annihilates space.” It does. It annihilates one of the most glorious gifts we have been given. It is a vile inflation which lowers the value of distance, so that a modern boy travels a hundred miles with less sense of liberation and pilgrimage and adventure than his grandfather got from traveling ten. Of course if a man hates space and wants it to be annihilated, that is another matter. Why not creep into his coffin at once? There is little enough space there.

— C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life

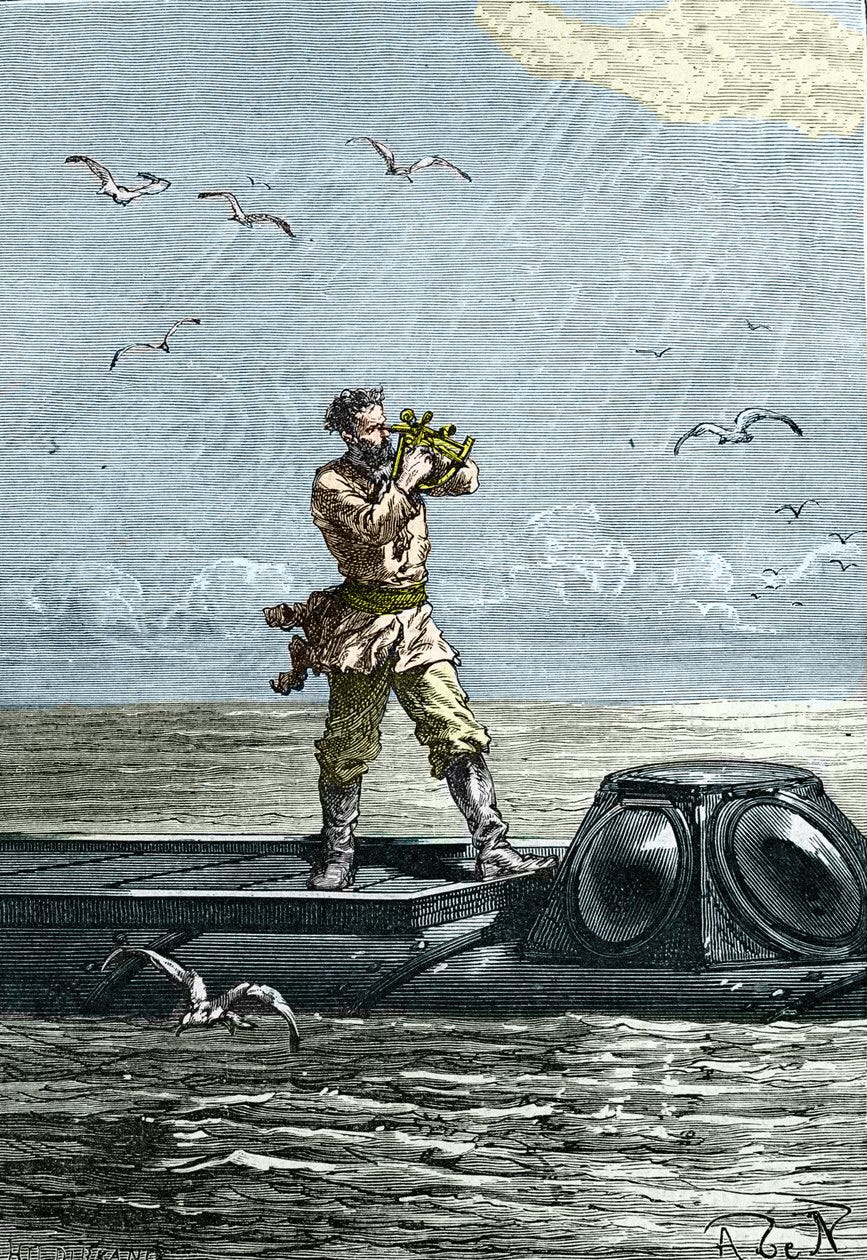

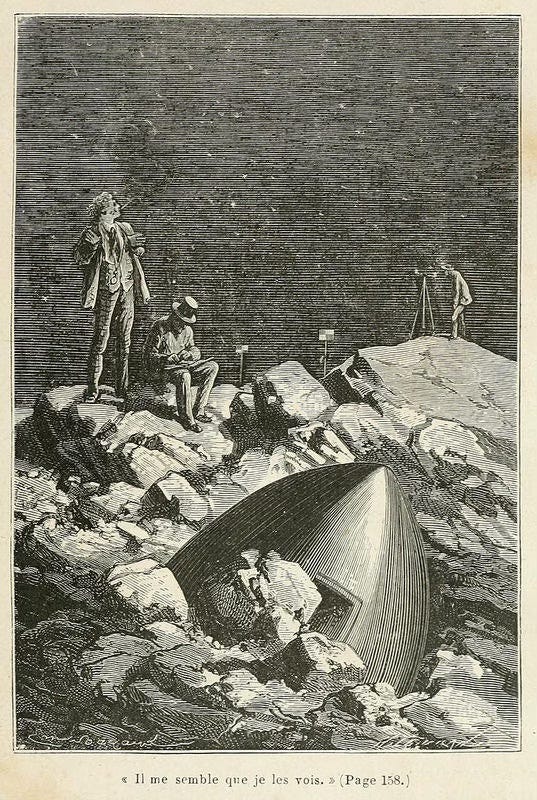

Adventure stories written before (or set before) the advent of wide-spread use of global transportation have a special wonder to them that is lost in our own lives now, because we are almost incapable of experiencing it. I think of books like Treasure Island, The Call of the Wild, The Swiss Family Robinson, Louis L’Amour’s westerns, C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Adventures, even children’s books like James and the Giant Peach and By the Great Horn Spoon!

Travel in these stories is not just an inconvenient obstacle to get past, but a character in its own right. Movement informs the characters’ decisions, builds the plot, and gives space to the storytelling; quite often, it is binding glue of it all, the wonder that draws us in. Ships battle against the seas on long journeys, cowboys or outlaws ride days across the desert on horseback, heroes walk the length of the moon and back to save the world, or go on madcap adventures by way of hot air balloon, steamer, camel, giant fruit, or foot. The in-between matters as much as the beginning and the end.

We do not live in this kind of world anymore. The in-between doesn’t matter, because we can’t see it, hidden there under a mass of clouds and 35,000 feet of distance, hidden by the darkness outside your red-eye flight, hidden behind the Benadryl taken to knock you out so you don’t have to experience the inconvenience of ten straight hours of travel. Traveling distances is as common as dirt. It’s an expectation. An inconvenience.

Here are a few numbers given (proudly) by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Over ten million passengers fly every year to and from 19,633 airports (3/4ths of which are private) on 45,000 daily average flights, of which 5,400 are in the sky T peak operational times. Almost three million passengers fly in and out of airports every day in the U.S. alone.

In comparison, I typically walk 3-4 miles per day on average, other than occasional 6-10 mile jaunts that usually end in pain and a rest day to recoup. That’s only a little under 1,500 miles each year spent on my feet using my own built-in locomotion to get from here to there. And these walks, for the most part, are voluntary acts of exercise with no particular destination in mind but to reach a landmark and turn back again, to ‘get my steps in’ so I can justify sitting for the rest of the day doing computer work.

But, since I have moved to this city and no longer have a car, I find myself walking much more. I walk to the library, to get groceries, to the bookshop, post-office, campus (sometimes) and coffee shops, and I’ve come to appreciate the time I have to travel these short distances on foot. I have become so much more familiar and intimate with my surroundings. I know street names. I know how long it takes me to go the short way or the long way. I know where the two pairs of swans spend their mornings and their afternoons. I have a map in my mind, drawn by my feet. It connects me to my paths by the soles of my shoes, by the movement of muscles.

Miles have changed. They have become shorter. I can go further, and the further I go the more I want to continue walking, to see what lays around the next bend, to see more of the secret, wild quiet places of this country. I want to walk and I don’t want to stop.

A few months ago at a small Sunday service in an old church I met three pilgrims. I was surprised at the use of this word by the other members of the congregation, because I’d never heard a modern person referred to as a ‘pilgrim’ before (that association was left to the Mayflower, broad-brimmed hats and white bonnets). They were walking the Becket Way from Southwark to Canterbury, following the Pilgrim’s Way; a 90 mile journey taking 11 days. There is something about the idea of leaving home, the blend of spiritual and physical, and what is found along the way. The use of feet and mind together. The concept of movement, of travel, and growth, of ambulation and design, combining the mental with the physical. I keep thinking about them, and the thousands of other people who complete pilgrimages each year to my city, and I wonder what goes through their minds as they do it; their reasoning, their justification, their goals.

I am reminded of Raynor Winn’s book Landlines. Her husband, Moth, was diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration, a rare neurological disease where the brain degenerates in a way similar to Alzheimer’s. Life expectancy after diagnosis is 6-8 years. In a desperate endeavor to stave off the end, the two of them embarked on a 1000 mile journey, on foot, from the north coast of Scotland to their home in Cornwall, in the southwest of England. They walked. And they walked. And they walked. It was painful at times, and seemed impossible, but the followed the lines of the land, for miles, because what else was there to do?

Irrational, irresponsible, maybe, but in that desperate moment our decision to walk offered every thing we needed — shelter in the form of our tent and a line on a map to follow. It gave us a route forward, a purpose, a reason to go on into the next day when all other reasons had fallen away.

— Raynor Winn, Landlines

But then the impossible actually happened—he got better. Now, neurodegenerative diseases don’t just go away, but through walking and movement, through air and wildness and open sky, Moth’s brain repaired itself, astonishing doctors. A miracle was given a chance to happen, and it happened. Every time I think about this book and Raynor and Moth’s journey, I experience wonder, and I think of what could be if movement, travel, and walking, was as revered of a medicine as any prescriptions or therapies. We have annihilated space and now we shun it, when it has so much to give.

We are ambulatory creatures. There is healing in walking. There is design behind step-taking that works both in our brains and our bodies, tying broken threads, loosening too-tight screws, waxing and waning in the constellation of the mind. Tides wash the dark spots clean. Movement feeds muscle and bone, tissue and neurons. What would happen if we were to recover space? If we were to reverse annihilation and reclaim the act of walking? Of acknowledging travel, of taking the slow ways, the tough ways, the pathless ways? I think we might find something of ourselves that has long been lost.

It’s the idea that the action of walking for a long time allows the world to fall away; eventually the walker and the path become one, the walker reaches the wayless way.

— Raynor Winn, Landlines